赞

相关文章

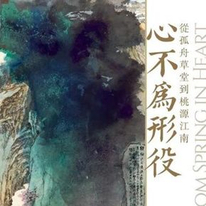

- 2024-08-29 10:04:432024 艺览北京

- 2024-08-29 10:02:422021 遇见弘裔

- 2024-08-28 16:34:202017 弘书演道

- 2024-08-28 16:36:502017 浦东电视台专访 一心书法艺术展-缅怀大师传承经典

- 2024-08-28 16:25:53遇见弘裔·一心书法作品集 序

- 2024-08-28 16:20:48Dai Xiaojing

作品推荐

展览推荐

拍卖预展

- 2022年春季艺术品拍卖会

- 安徽省艺观拍卖有限公司

- 预展时间:2030年12月31日

- 预展地点:安徽省芜湖市萧瀚美

- 北京盈昌当代书画专场(十

- 北京盈昌国际拍卖有限公司

- 预展时间:2022年3月21日-30日

- 预展地点:北京盈昌网拍

- 北京盈昌当代书画专场拍卖

- 北京盈昌国际拍卖有限公司

- 预展时间:2022年3月21日-27日

- 预展地点:北京盈昌网拍

官网推荐

拍卖指数

每日最新

- [新闻] 【艺见】 路琼:温柔的视觉抵抗——刘少磊作品中的女性精神与视觉隐喻

- [拍卖] 嘉选三月“中国书画”专场,古代书画珍赏

- [画廊] WKM Gallery 新展预告:一位加拿大摄影师眼中的香港与东京四十年

- [展览] 现场 | 在存在与记忆之间:《她在 | Landscapes of Being》——以绘电索尼娅·佩耶斯双人展悉尼朱雀艺术启幕

- [观点] 杨福音:福音杂货铺(五十三)

每周热点

- 1 艺术品消费“吃快餐”,远离了傲慢还

- 2 守护诚信 致力传承,雅昌鉴证备案以领

- 3 央视3·15曝光疯狂的翡翠直播间:古玩

- 4 张大千剧迹《仿王希孟千里江山图》睽

- 5 “写实主义与超现实主义的对话--孙家

- 6 佳士得纽约亚洲艺术周 | 重要大理国铜

- 7 Poly-Online丨“春意”上线——中国

- 8 XR技术与艺术创作融合的元宇宙虚拟

- 9 专稿 | 是什么成就了加埃塔诺·佩谢

- 10 艺术号·专栏 | 陈履生:画中的少数

排行榜

论坛/博客热点

- 展台上的瓷塑 千军万马战犹酣

- 以藏养藏做再好 终究不如实力雄厚的真玩家?

- 古人烧瓷有讲究 入窑前以煤油遮面以防被偷窥

- 吴伟平:艺术创作,开启了一场没有陪伴的旅

- 杜洪毅:艺术圈里的文字游戏 当代艺术看不懂

推荐视频

业务合作: 010-80451148 bjb@artron.net 责任编辑: 程立雪010-80451148